|

|

CHANCE SYNCHRONICITY & MIND-WRITING:

Write About a Spiritual Crisis or Transformation

I underwent, during the summer that I became fourteen, a prolonged religious crisis. I use the word “religious” in the common, and arbitrary, sense, meaning that I then discovered God, His saints and angels, and His blazing Hell. And since I had been born in a Christian nation, I accepted this Deity as the only one. I supposed Him to exist only within the walls of a church—in fact, of our church—and I also supposed that God and safety were synonymous. The word “safety” brings us to the real meaning of the word “religious” as we use it. Therefore, to state it in another, more accurate way, I became, during my fourteenth year, for the first time in my life, afraid—afraid of the evil within me and afraid of the evil without. What I saw around me that summer in Harlem was what I had always seen; nothing had changed. But now, without any warning, the whores and pimps and racketeers on the Avenue had become a personal menace. It had not before occurred to me that I could become one of them, but now I realized that we had been produced by the same circumstances. Many of my comrades were clearly headed for the Avenue, and my father said that I was headed that way, too. My friends began to drink and smoke, and embarked—at first avid, then groaning—on their sexual careers. Girls, only slightly older than I was, who sang in the choir or taught Sunday school, the children of holy parents, underwent, before my eyes, their incredible metamorphosis, of which the most bewildering aspect was not their budding breasts or their rounding behinds but something deeper and more subtle, in their eyes, their heat, their odor, and the inflection of their voices. Like the strangers on the Avenue, they became, in the twinkling of an eye, unutterably different and fantastically present. Owing to the way I had been raised, the abrupt discomfort that all this aroused in me and the fact that I had no idea what my voice or my mind or my body was likely to do next caused me to consider myself one of the most depraved people on earth. Matters were not helped by the fact that these holy girls seemed rather to enjoy my terrified lapses, our grim, guilty, tormented experiments, which were at once as chill and joyless as the Russian steppes and hotter, by far, than all the fires of Hell.

Yet there was something deeper than these changes, and less definable, that frightened me. It was real in both the boys and the girls, but it was, somehow, more vivid in the boys. In the case of the girls, one watched them turning into matrons before they had become women. They began to manifest a curious and really rather terrifying single-mindedness. It is hard to say exactly how this was conveyed: something implacable in the set of the lips, something farseeing (seeing what?) in the eyes, some new and crushing determination in the walk, something peremptory in the voice. They did not tease us, the boys, any more; they reprimanded us sharply, saying, “You better be thinking about your soul!” For the girls also saw the evidence on the Avenue, knew what the price would be, for them, of one misstep, knew that they had to be protected and that we were the only protection there was. They understood that they must act as God’s decoys, saving the souls of the boys for Jesus and binding the bodies of the boys in marriage. For this was the beginning of our burning time, and “It is better,” said St. Paul—who elsewhere, with a most unusual and stunning exactness, described himself as a “wretched man”—”to marry than to burn.” And I began to feel in the boys a curious, wary, bewildered despair, as though they were now settling in for the long, hard winter of life. I did not know then what it was that I was reacting to; I put it to myself that they were letting themselves go. In the same way that the girls were destined to gain as much weight as their mothers, the boys, it was clear, would rise no higher than their fathers. School began to reveal itself, therefore, as a child’s game that one could not win, and boys dropped out of school and went to work. My father wanted me to do the same. I refused, even though I no longer had any illusions about what an education could do for me; I had already encountered too many college-graduate handymen. My friends were now “downtown,” busy, as they put it, “fighting the man.” They began to care less about the way they looked, the way they dressed, the things they did; presently, one found them in twos and threes and fours, in a hallway, sharing a jug of wine or a bottle of whiskey, talking, cursing, fighting, sometimes weeping: lost, and unable to say what it was that oppressed them, except that they knew it was “the man”—the white man. And there seemed to be no way whatever to remove this cloud that stood between them and the sun, between them and love and life and power, between them and whatever it was that they wanted. One did not have to be very bright to realize how little one could do to change one’s situation; one did not have to be abnormally sensitive to be worn down to a cutting edge by the incessant and gratuitous humiliation and danger one encountered every working day, all day long. The humiliation did not apply merely to working days, or workers; I was thirteen and was crossing Fifth Avenue on my way to the Forty-second Street library, and the cop in the middle of the Street muttered as I passed him, “Why don’t you niggers stay uptown where you belong?” When I was ten, and didn’t look, certainly, any older, two policemen amused themselves with me by frisking me, making comic (and terrifying) speculations concerning my ancestry and probable sexual prowess, and for good measure, leaving me flat on my back in one of Harlem’s empty lots. Just before and then during the Second World War, many of my friends fled into the service, all to be changed there, and rarely for the better, many to be ruined, and many to die. Others fled to other states and cities—that is, to other ghettos. Some went on wine or whiskey or the needle, and are still on it. And others, like me, fled into the church.

James Baldwin, from The Fire Next Time.

THE SKIN OF LIGHT

The skin of light enveloping this world lacks depth and I can actually see the black night of all these similar bodies beneath the trembling veil and light of myself it is this night that even the mask of the sun cannot hide from me I am the seer of night the auditor of silence for silence too is dressed in sonorous skin and each sense has its own night even as I do I am my own night I am the conceiver of non-being and of all its splendor I am the father of death she is its mother she whom I evoke from the perfect mirror of night I am the great inside-out man my words are a tunnel punched through silence I understand all disillusionment I destroy what I become I kill what I love.

- Rene Daumal (tr. by Michael Benedikt)

- To Love is to Confess We are Loved

To love is to confess we are loved. Our life is a catastrophic encounter between two types of time in which only one can survive. The inducement of love as a dark storm collapses hope and fear and leaves us islanded without the objects we once stared into imagining permanence. The evolution of each single life has no agreed upon beginning. We journey through understanding: first words, their meaning, rules, lessons, responsibilities, everyone's opinion of us internalized mirror becoming finally transparent with our last breath. Time is a fire so bright it leaves no shadow. We cannot accept that we don't know what will happen. We scratch at it. We measure it, or curse. Time does not understand words. Under its spotlight we are refused our own meaning. When we confess we are loved.

- - Bill Scheffel 9-March: 2011 Paris

Moon Lake of Enlightenment

For the last ten years, the single most important person in my life has been invisible to me, except once. When she appeared. Much later I named her Moon Lake of Enlightenment.

As befitting an invisible mother, she has driven me crazy. First in an attempt to find her, following the bread crumbs of coincidence through Rome and Istanbul, and into Cambodia.

And then after I did find her, was she too much to bear? She is many people: the guru's doppelgänger, anima, lover, commander, apparition. The most beautiful woman I have ever met.

I found her in Phnom Penh, with its near lawless streets, prostitution and atmosphere of impunity. Phnom Penh, city of temples, colonialism and new opportunity. Ghost city. Execution ground. City of Rivers.

Someone or something insisted I find her. I left my job, my home, eventually even my clothes. Reduced to a suitcase I still remained smitten. Seeking her, I drank too much wine.

In a cheap hotel room she appeared and made me promises. That she would be with me until enlightenment. I felt protected and safe. Even invincible. I let her come though my handwriting. I wanted to share her.

Like the spinning wheels of a slot machine I had no idea where I would land, much less the fate that had me in store. I had no idea what enlightenment meant. How far that shore. How crazy my mind.

Each morning I never stopped praying to the guru and Moon Lake of Enlightenment. I lost all my furniture and accoutrements. Wandered back to Istanbul. I was almost killed by a streetcar.

Along with the streetcar, a seizure left me comatose and a suffering in my lonely stomach caused heat and cold to inverse and I nearly froze to death. I think she has found it all amusing.

When I stare into the coffee grinds I see a flaming salamander. Thanks to poetry I found Moon Lake of Enlightenment. Poetry taught me to love the liminal, the marginal, the alluvial.

My question to her today is, What have I done? I have no job, no status, no home, no youth, dwindling money and a passport. Where is the enlightenment in this?

My question to her today is, What should I regret? She is fiery in her reply, a double-edged sword. I am with you until enlightenment. Give up everything, you've already gone crazy, gone broke, gone wandering.

But your self is persistent, an ego clinging to a burned out campfire or melting ice sheet. I'll send you back to Cambodia, Istanbul, Crestone. You will continue to wander, the job that suits you.

I've have not been satisfied. Are her answers merely my imagination? My friends understand me. They have faith in her. I have faith. On the oil-stained streets of Phnom Penh I felt her afterglow.

She appeared slowly as I wandered from Bangkok to Sihanoukville and then to Phnom Penh. Each day in meditation she dropped a new clue. Sometimes she told me to get a good meal. And then she began to emerge.

From her intangible birth canal she showed my her parasol, her cat eyes, her braided black hair. The next day she appeared - ineffable, luminous, eternally loving, without an atom of distress, looking at me very close and indescribably present.

Later on, satisfied that she was with me I did get a meal. Hired a motorbike taxi, took a long walk after drinking sugar cane juice, got caught in the rain. Took shelter under the tarp of a Cambodian grandmother, another form of Moon Lake of Enlightenment.

She is a vision, a samaya holder, a seven day-long movie I had the privilege to watch ten years ago. Everthing has been falling apart since then, believe me. If you see her, please let me know.

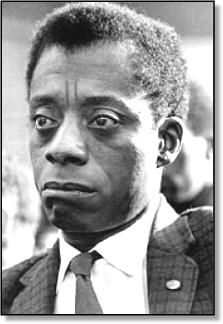

James Baldwin

Why Did the FBI Spy on James Baldwin

James Baldwin’s FBI file contains 1,884 pages of documents, collected from 1960 until the early 1970s. During that era of illegal surveillance of American writers, the FBI accumulated 276 pages on Richard Wright, 110 pages on Truman Capote, and just nine pages on Henry Miller. Baldwin’s file was closer in size to activists and radicals of the day — for example, it’s nearly half as thick as Malcolm X’s.

In his new biography, All Those Strangers, Douglas Field decodes these files with great literary and historical finesse. Baldwin often said that his relation to politics was that of a “witness,” but he was vehemently stalked, harassed and even censored by the FBI. Field asserts that after looking through Baldwin’s FBI file, it’s clear his phone was tapped and that government agents, posing as publishers or car salesmen, followed him as he traveled to France, Britain and Italy.

The biography has landed at a particularly sharp moment in our awareness of government surveillance. We now have not only the National Security Agency and its global spying, but the FBI and local law enforcement agencies targeting political activists, such as supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement. And the NYPD, for instance, has its own counterterrorism unit that has surveilled entire communities. Read more...

by Hanna K. Gold, fromThe Intercept

Ta-Nehisi Coates

"This is your country, this is your world, this is your body, and you must find some way to live within the all of it."

In a profound work that pivots from the biggest questions about American history and ideals to the most intimate concerns of a father for his son, Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a powerful new framework for understanding our nation's history and current crisis. Americans have built an empire on the idea of "race," a falsehood that damages us all but falls most heavily on the bodies of black women and men's bodies exploited through slavery and segregation, and, today, threatened, locked up, and murdered out of all proportion. What is it like to inhabit a black body and find a way to live within it? And how can we all honestly reckon with this fraught history and free ourselves from its burden?

Between the World and Me is Ta-Nehisi Coates's attempt to answer these questions in a letter to his adolescent son. Coates shares with his son's and reader's the story of his awakening to the truth about his place in the world through a series of revelatory experiences, from Howard University to Civil War battlefields, from the South Side of Chicago to Paris, from his childhood home to the living rooms of mothers whose children's lives were taken as American plunder. Beautifully woven from personal narrative, reimagined history, and fresh, emotionally charged reportage, Between the World and Me clearly illuminates the past, bracingly confronts our present, and offers a transcendent vision for a way forward.

From an Amazon.com description.

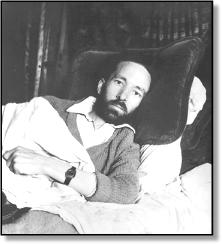

Rene Daumal

Rene Daumal was born in Boulzicourt, Ardennes, France. In his late teens his avant-garde poetry was published in France's leading journals, and in his early twenties, although courted by André Breton co-founded, as a counter to Surrealism and Dada, a literary journal, "Le Grand Jeu" with three friends, collectively known as the Simplists, including poet Roger Gilbert-Lecomte . He is best known in the English-speaking world for two novels: A Night of Serious Drinking, and the allegorical novel Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing, both based upon his friendship with Alexander de Salzmann, a pupil of G. I. Gurdjieff.

Daumal was self-taught in the Sanskrit language and translated some of the Tripitaka Buddhist canon into the French language, as well as translating the literature of the Japanese Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki into French.

He married Vera Milanova, the former wife of the poet Hendrik Kramer; after Daumal's death, she married the landscape architect Russell Page.

Daumal's sudden and premature death from tuberculosis on 21 May 1944 in Paris may have been hastened by youthful experiments with drugs and psychoactive chemicals, including carbon tetrachloride. He died leaving his novel Mount Analogue unfinished, having worked on it until the day of his death.

![]()